As China lifted a 25-year ban on the trade of tiger bones and rhino horn last month, sale of endangered wild animal parts remains rife on and off the Chinese internet.

This story is part of the ‘Reporting the Online Trade in Illegal Wildlife’ programme, a joint project of the Thomson Reuters Foundation and The Global Initiative Against Organized Crime funded by the Government of Norway.

Tiger bone, bear bile, deer musk and pangolin scales are all prized ingredients in traditional Chinese medicine. They also come from some of the most endangered species of animals on earth, whose international trade is protected by the Convention on Illegal Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES). But on Chinese social media and e-commerce platforms, their sale is still rife.

For instance, deer musk, an odorous secretion from the male musk deer, is believed by the Chinese to be of high medicinal value. Over the past 50 years, the poaching of musk deer has been so rampant in China that their population has shrunk by more than 90 per cent. Although the government gave the species class I protection status in 2003, it is still allowing more than 10 pharmaceutical companies to legally use natural musk – either from their own stockpiles or farmed musk deer – in nearly 20 products.

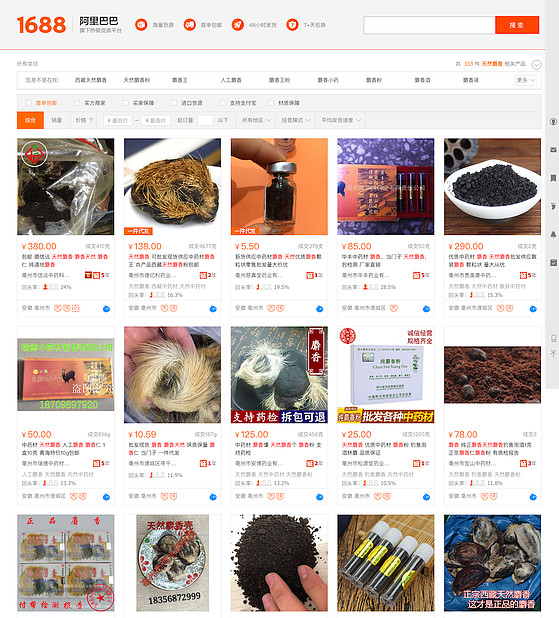

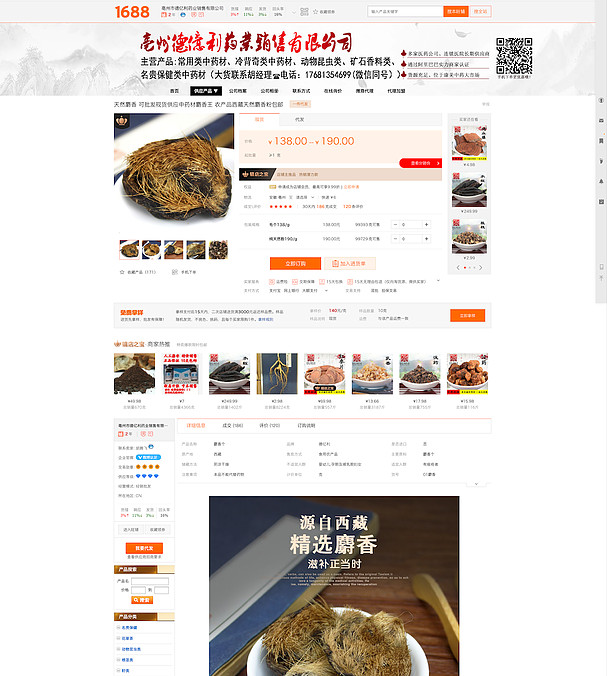

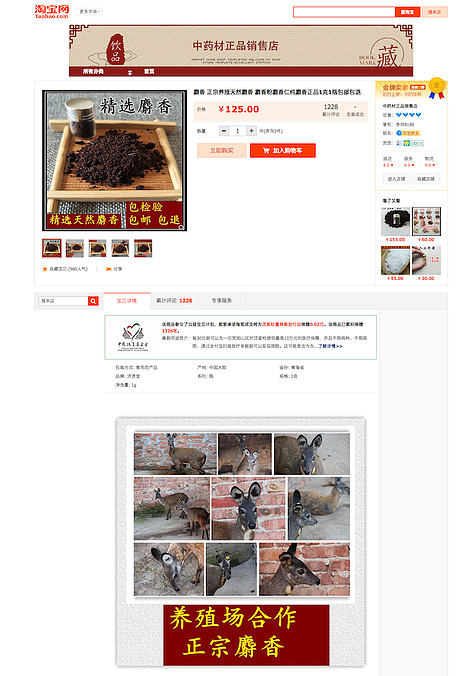

It is easy to buy illegal raw musk on the internet too. On Alibaba’s 1688.com and Taobao, at least a dozen postings can be found offering to sell raw musk pods or powders – ostensibly from Qinghai or Tibet – all without proper documentations, including a special label required to be displayed on the packaging of legal products. Most of the sellers are based in Bozhou, Anhui, which is dubbed one of the “four medicinal capitals of China”. Advertised as “healthy and nourishing,” these items have been sold to at least 5,000 people according to the number of reviews left by buyers.

These online transactions are illegal and completely “off the books”, admits one seller. “Products with proper documents cost twice as much,” he says. “They are only crude drugs. I don’t need a licence to sell farm produce,” another trader argues, before abruptly hanging up when questioned about musk deer being a Class I protected species.

According to officials at the Chinese State Forestry Administration, Anhui Forestry Department and Bozhou Forestry Bureau, it is illegal to trade raw musk without approval or to sell it to retail customers, while legal pharmaceutical products that contain deer musk must bear a special label issued by the government. Alibaba has now removed listings that mention natural musk in their descriptions from 1688.com and Taobao following an enquiry from FactWire. “We will also continue to take action against sellers who violate laws or our product-listing policy,” a spokesperson says.

Relentless online sales

In November last year, Chinese internet giants Baidu, Alibaba and Tencent joined forces with eight other e-commerce companies to launch a massive campaign, vowing to curb the rampant online sales of endangered wildlife. But its effectiveness is questionable.

On Baidu Tieba, a Chinese discussion platform similar to Reddit, keywords such as rhino horns, antelope horns and bear gile, which are banned from sale in China, are directly blocked from appearing in search results, but adverts for endangered wildlife parts can still be found by adding words like curio or crude drugs, or using their homophonic characters or pinyin.

Buyers and sellers typically hide their identity by only leaving their usernames on Wechat in the adverts and transacting through online payment methods and courier services. One seller on Wechat can offer deer musk, bear bile, tiger bones and antelope horns, while flaunting them as a cure for everything; Another seller claims to be a wooden furniture merchant but is able to source frozen or live pangolins and their scales from Vietnam and Laos. “They are all freshly killed,” he boasts on the messaging app.

Voracious appetite

Thanks to an insatiable demand for wild animals in China, illegal poachers, traffickers, smugglers and sellers from all corners of the country have formed a powerful supply chain. The trafficking of pangolins, for example, is very difficult to track. In one case that happened between 2013 and 2014, the defendant paid three groups of smugglers to move 2,200 pangolins from Vietnam across the border into Guangxi using boats and motorcycles, and then delivered them to Guangdong using private vehicles.

The habit of eating wild animals stretches back centuries in China and is very much part of the Cantonese cuisine. After the 2003 SARS outbreak, which was initially thought to originate from exotic animals – such as palm civets and raccoon dogs – the provincial government stepped up its efforts to curtail wildlife consumption by banning party members and officials from eating them. But such discouragement has so far proven to be futile.

“The culture of eating rare species spreads from the top to bottom,” says a wildlife volunteer, who has only given his name as Yiyun for fear of his safety. “People think eating them is a status symbol and good for their health. In every Chinese city there is always a street full of restaurants where you can pre-order wild animal meat.”

For many years Yiyun has teamed up with other volunteers, going undercover as diners and reporting these restaurants to authorities. In one operation in March they found two ailing pangolins, which were believed to have been force-fed water to increase their weight, in order to fetch a higher price. “It was upsetting, I was still holding it in my hand… The pangolin is a slow and shy species. it will just curl up into a ball when it is attacked, so its life is very fragile,” he laments.

Underground trade

According to the observations of Yiyun and another volunteer who goes by the name Yuexin, in every Chinese city there are at least 10 black markets that supply wild animal parts to nearby restaurants. These marketplaces are typically used for legal agricultural wholesale in daytime but are converted into seedy wildlife markets at night.

Last year, volunteers successfully tracked down pangolin traffickers to a poultry trading market in Guangzhou, which has since been shut down following media reports. But some appear to have stayed behind. In dark and empty streets, a few mini lorries typically used for transporting wild animals can still be seen parked next to what used to be wildlife shops. Within minutes, one lady has turned up in her motorcycle in suspicion.

More than an hour’s drive away is another market called the Furong agricultural wholesale market. At midnight, the air reeks of animal flesh and feces; wild sounds echo through dimly lit shops. Inside cages lining the corridors are live wild animals like porcupines and masked palm civets – both are protected species but can be legally sold with licences – and many more that are indistinguishable in the dark.

These shops only display legal wild animals at the front and keep endangered species like pangolins hidden. To conduct a trade, buyers often place an order on Wechat first. They will then park deep inside the market at night and directly transfer the animals from one vehicle to another.

Bitter pills, unproven remedies

For years activists in China has been promoting the message that “when the buying stops, the killing can too”, but many now fear that the government’s recent reboot of its wildlife law in 2017, which has provisions that allow for endangered animal farming and trading for medicinal use, has left loopholes for the use of wild animal parts that were originally tightly restricted to thrive again.

For example, although in 2016 the critically endangered pangolin was elevated to CITES Appendix I – the highest protection status, the use of pangolin scales is still legal in 700 Chinese hospitals and around 70 medicines manufactured by authorised drug companies. Activists have criticised the lack of transparency about their sales volume and inventory, which enables smuggled scales to enter the market easily.

Processed pangolin scales are also still commonly sold in pharmacy chains in China. In a chemist in Guangzhou, a salesperson says these scales not only can reduce swelling, but also help with lactation and blood circulation.

However, according to Professor Lao Lixing, director of the School of Chinese Medicine at the University of Hong Kong, many animal-based remedies were historically only based on the shapes and behaviours of the animals. “For example, people used to believe pangolins, which dig through the ground using their claws, can help blood circulate; Or since tigers are strong, they must have extraordinary health benefits too,” he says.

Lao, who has also studied western physiology, believes that animal parts should no longer have a place in traditional medicine. “First, there are many substitutes for animal parts. Second there is no proof that animal-based remedies are better than other methods. Third, even if animal parts are proved to be useful, human beings should not put their self-interest above the welfare of animals,” he says, adding that the perceived health benefits of pangolin scales, for instance, can be replaced by more than 20 medicinal herbs.

Lao lambasts that traffickers would exaggerate the benefits of wild animal parts in order to extract higher prices, for example by concocting folk remedies like pangolin meats and pangolin blood with rice, which have no medical evidence.

Trafficking and enforcement

According to the International Union for Conservation of Nature, a total of one million wild pangolins were poached and illegally traded globally between 2004 and 2014. Trafficking of pangolin parts has remained rampant despite repeated crackdowns, with Hong Kong being an important port in the entire value chain.

According to government data, between 2015 and August 2018, Hong Kong customs officials seized over 45 tonnes of pangolin scales estimated to be worth more than HK$80m – meaning that at least 22,000 pangolins were slaughtered in three years, given that one can produce about 500g of scales. The smuggling of pangolins has shown no sign of abating: in the first eight months of 2018 alone, Hong Kong has seized a total of 16 tonnes – the highest figure in five years – including 11.7 tonnes found hidden in several 40-foot shipping containers originated from Nigeria in three separate seizures.

“Demand for pangolin scales is low in Hong Kong, so these specimens were probably destined for neighbouring areas such as mainland China,” says Chan Tsz-tat, head of the Customs and Excise Department’s ports and maritime command.

These successful seizures and convictions only represent the tip of the iceberg, considering the scale of the illegal wildlife trade. In Hong Kong, for instance, only 20 cases involving the smuggling of pangolins were successfully prosecuted between 2014 and early 2018, with the most severe penalty being two months of imprisonment. Taking a stronger stance against endangered wildlife trafficking, the Hong Kong government has recently updated its law to increase the maximum penalties from a fine of HK$5m to HK$10m and from two years of imprisonment to 10 years.

Meanwhile in China, the government has finally upped the ante against the booming online wildlife trade. For example in last year’s revision of the wildlife protection law, e-commerce platforms were for the first time made liable for any illegal wild animal goods sold by vendors on their websites. These platforms and online traffickers were also targeted earlier this year in a nationwide enforcement campaign, which, in one case, saw a man in Guangzhou arrested for allegedly selling 168 protected wild animals online, including a globally threatened rhinoceros iguana.

But for the volunteer groups that investigate the illegal sales of wild animals – both on or off the internet – it remains dangerous work. Both Yiyun and Yuexin have received threatening calls and messages, so they must be careful in every operation. “The truth is, some government officials don’t like us, the public don’t understand us. There is pressure everywhere,” Yuexin says.

This story was produced by FactWire written as part of the ‘Reporting the Online Trade in Illegal Wildlife’ programme. This is a joint project of the Thomson Reuters Foundation and The Global Initiative Against Organized Crime funded by the Government of Norway. More information at http://globalinitiative.net/initiatives/digital-dangers. The content is the sole responsibility of the author and the publisher.