In early March of this year, Eastern Hospital was found to have been administering unregistered antibiotics made in Mainland China. Upon further investigation, FactWire finds that the use of unregistered drugs at this hospital was not an exceptional case, and is actually rampant throughout Hong Kong.

In early March of this year, Eastern Hospital was found to have been administering unregistered antibiotics made in Mainland China. When questioned, the Hospital Authority explained that it was due to a shortage of a specific drug. Upon further investigation, FactWire finds that the use of unregistered drugs at this hospital was not an exceptional case, and is actually rampant throughout Hong Kong.

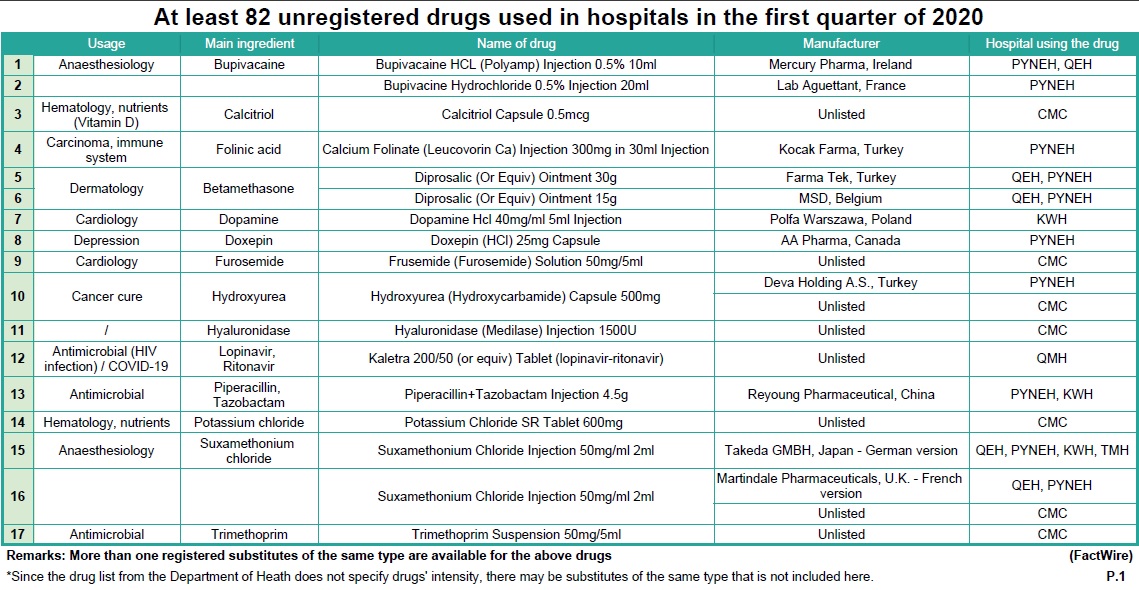

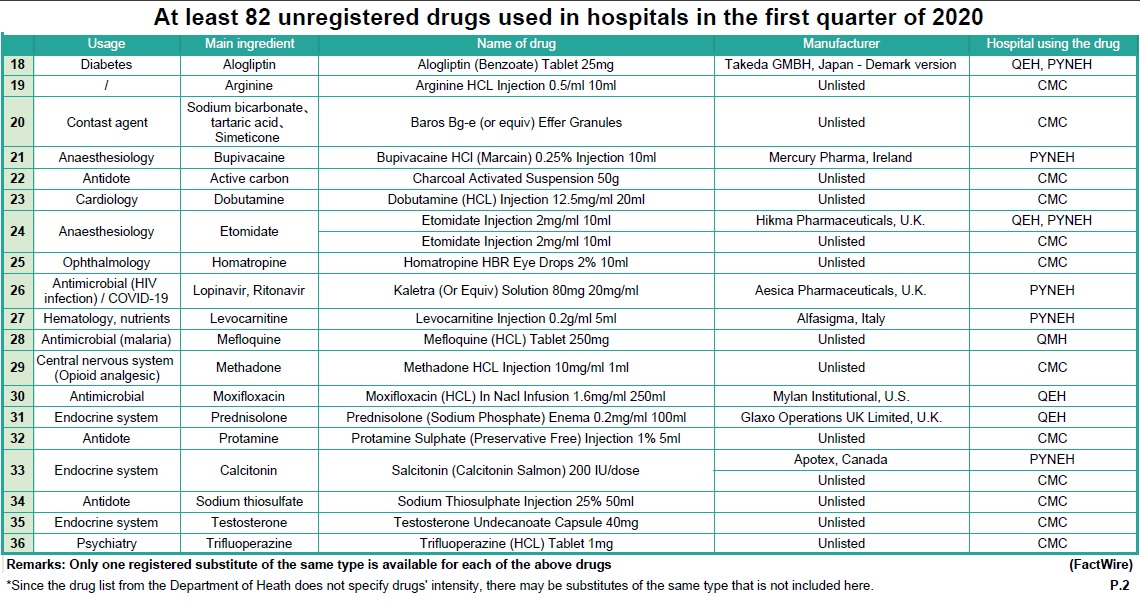

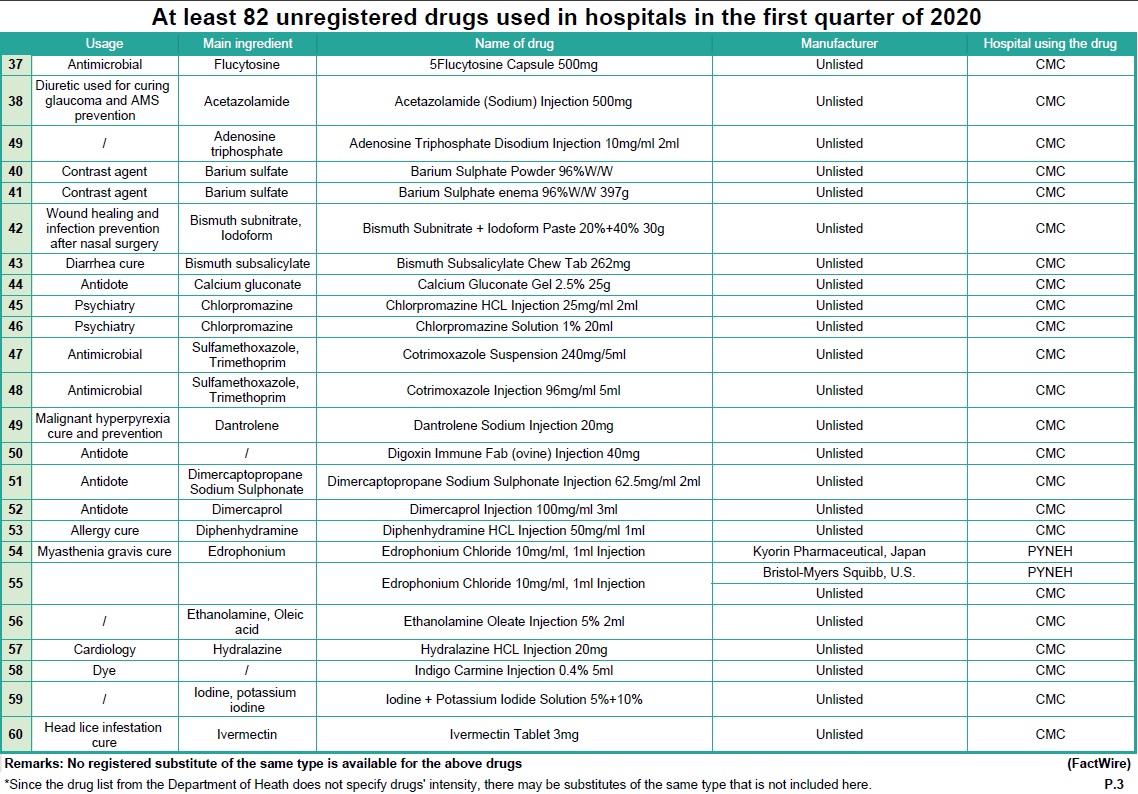

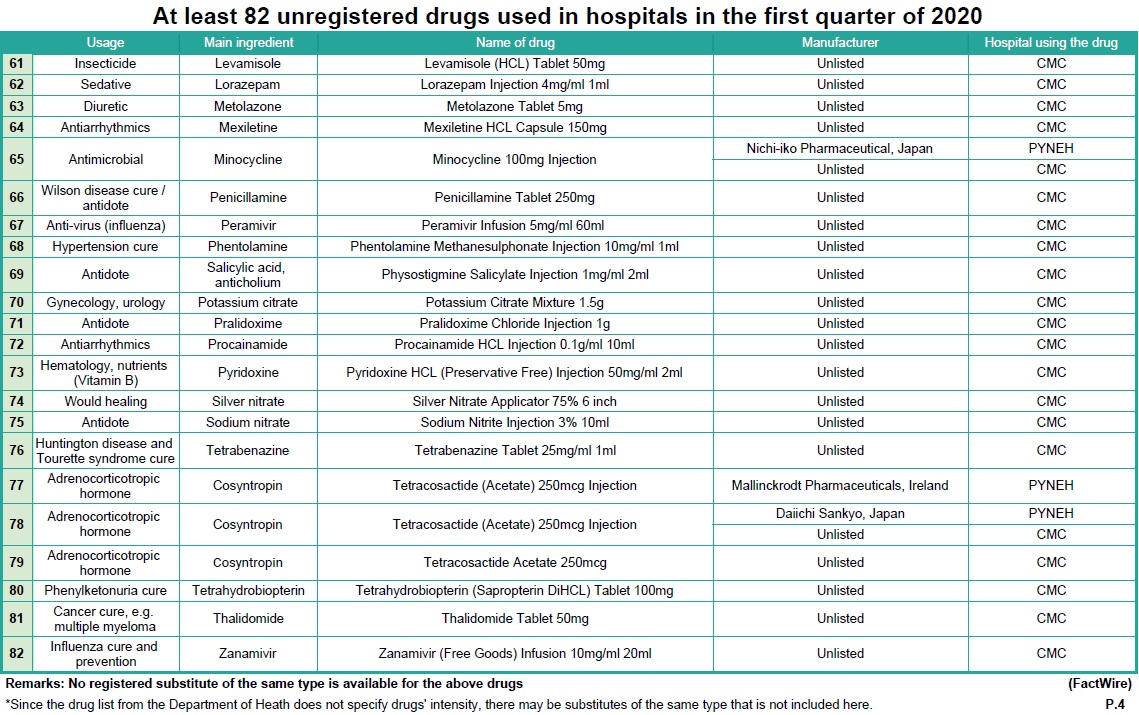

Using the internal documents of these hospitals, FactWire discovered at least 82 unregistered drugs that have been administered across six public hospitals in the first quarter of this year alone. An array of unregistered drugs ranging from antibiotics, dermatological medications, cancer treatments, and treatments for COVID-19 (see Table 1) have been used in Pamela Youde Nethersole Eastern Hospital (PYNEH), Queen Elizabeth Hospital (QEH), Caritas Medical Centre (CMC), Tuen Mun Hospital (TMH), Kwong Wah Hospital (KWH) and Queen Mary Hospital (QMH).

These unregistered drugs were processed through the ‘Named Patient’ programme, originally designated for introducing drugs that are new or for rare diseases. However, it is now being used by the Hospital Authority to introduce unregistered common drugs. One or more registered substitutions are available for at least 36 out of 82 drugs in Hong Kong, but it remains unclear why the Authority continues using unregistered options instead. No substitution of the same type is available for the other 46 drugs.

Patients, as well as doctors giving medical prescriptions, may not know that the drugs being used are unregistered. In fact, out of all six hospitals, only the internal emails of Queen Mary Hospital specified that the drugs were unregistered and that their safety, efficacy and quality had not been assessed. The other five hospitals did not issue relevant reminders to their medical staff despite the Department of Health’s advice to give warning to patients when administering unregistered drugs.

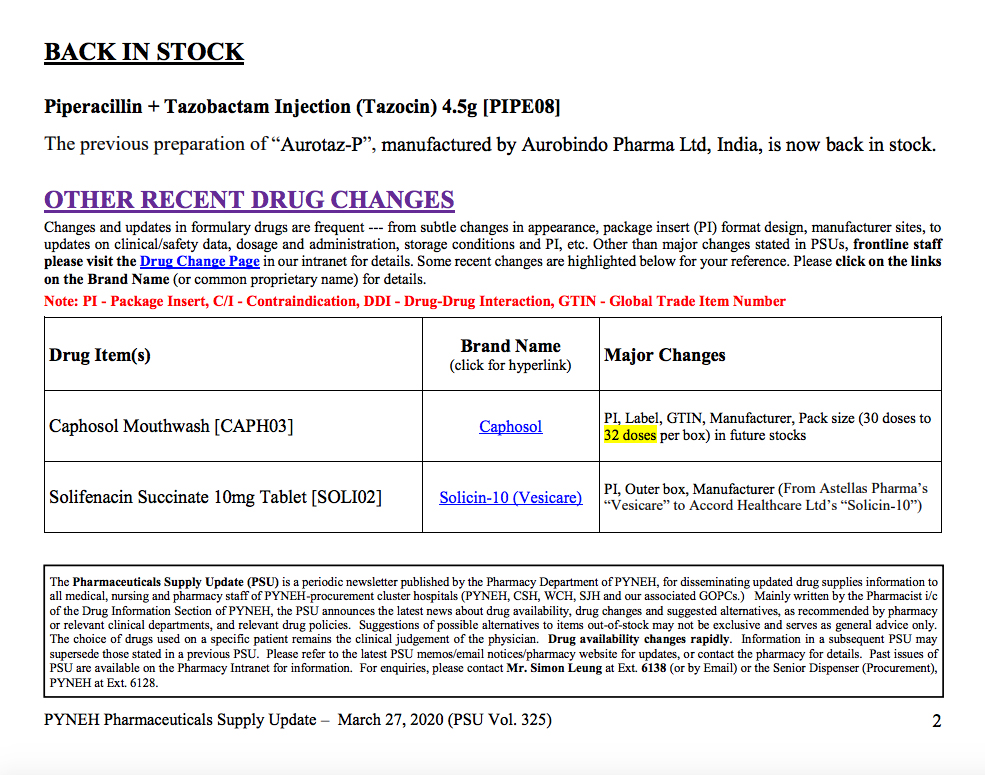

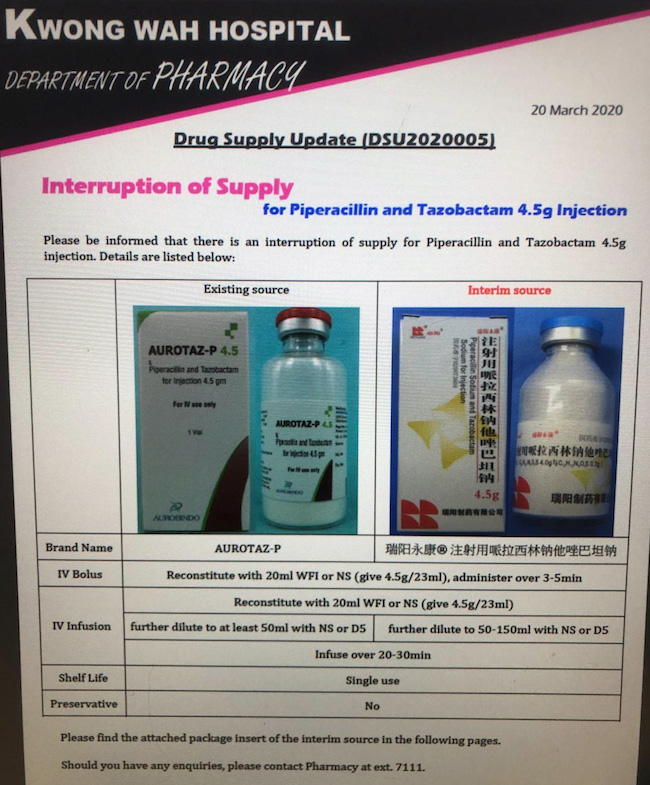

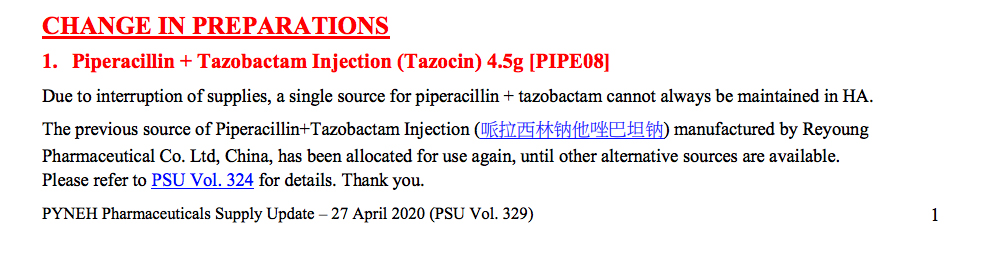

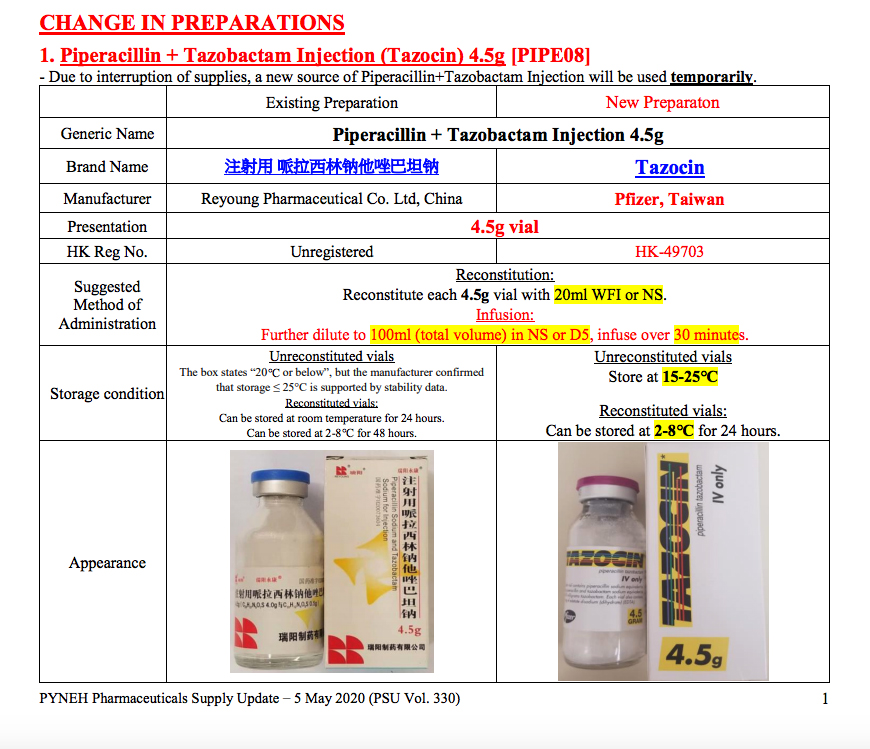

The unregistered drug that led to the exposure of Eastern Hospital was an antibiotic (Piperacillin + Tazobactam Injection 4.5g) produced in Shantung. The hospital’s internal records show that by March 27 it had been replaced with a registered drug substitute made by Aurobindo Pharma in India. However, only a week before March 27, another hospital, Kwong Wah, reported an ‘interruption of supply’ from the antibiotics made in Aurobindo Pharma, replacing them with those made in Shantung. A month after Eastern Hospital had replaced the unregistered Shantung-made antibiotics, they were used again in late April. It was not until early May that they were replaced with registered ones made in the U.S..

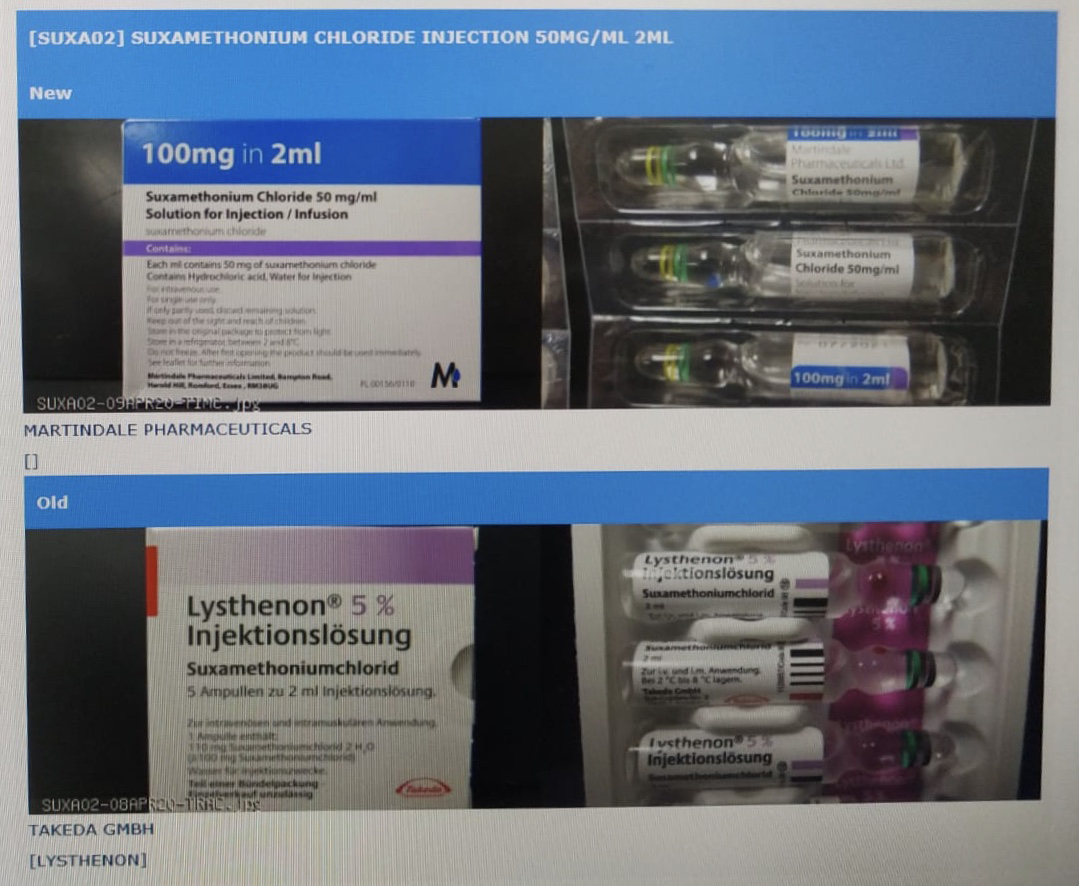

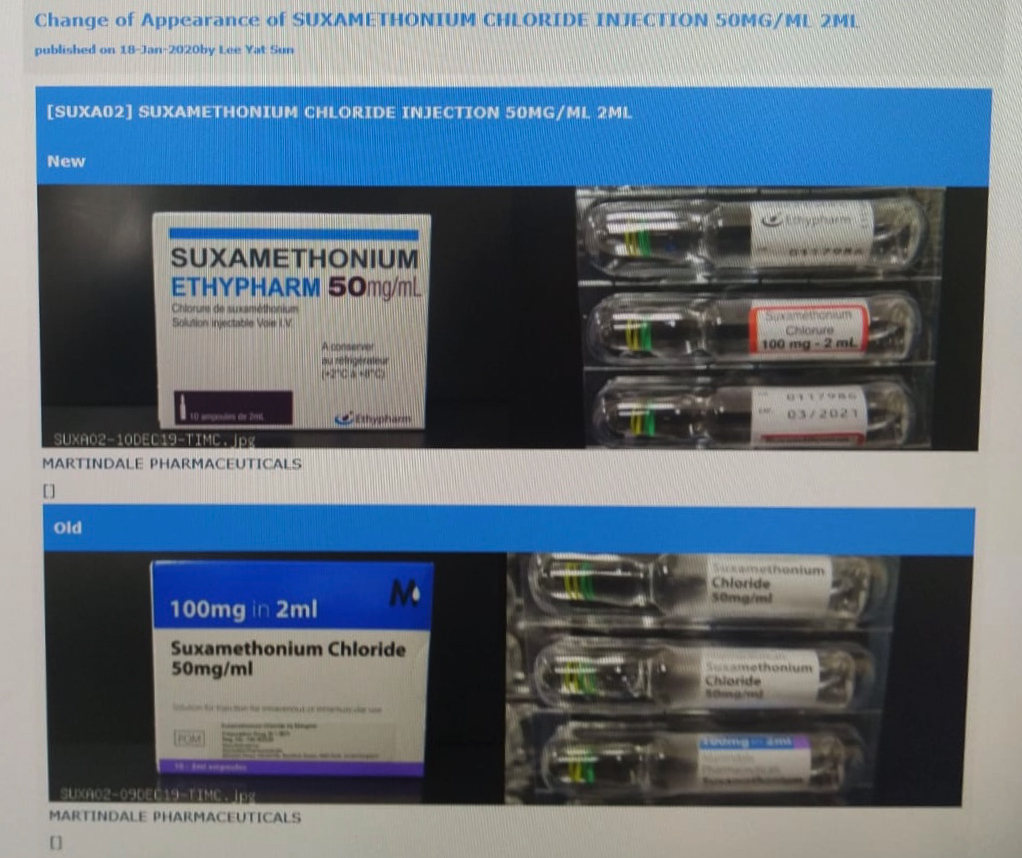

Similarly unregistered usage occurred with an anaesthetic drug, ‘Suxamethonium Chloride Injection 50mg/ml 2ml’. In this case, unregistered drugs that were actually meant for export to other places were used in Hong Kong. This unregistered anaesthesia is commonly used in five public hospitals: Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Eastern Hospital, Kwong Wah Hospital, Tuen Mun Hospital and Caritas Medical Centre. Notes circulated to medical staff in four out of the five hospitals show that the unregistered drug was produced in Japan’s Takeda GMBH. The place of production of the unregistered drug used in Caritas Medical Centre is unknown.

Before the change to the Japanese-made unregistered drug, Queen Elizabeth Hospital and Eastern Hospital had been importing another version of this drug made by Martindale Pharmaceuticals in the U.K.. The registered version of these drugs should come with English instructions and a registration code of ‘HK-60239’ on its package. However, FactWire’s investigation shows that the language of the packaging found in the two hospitals is French, with no corresponding registration record found in the Department of Health.

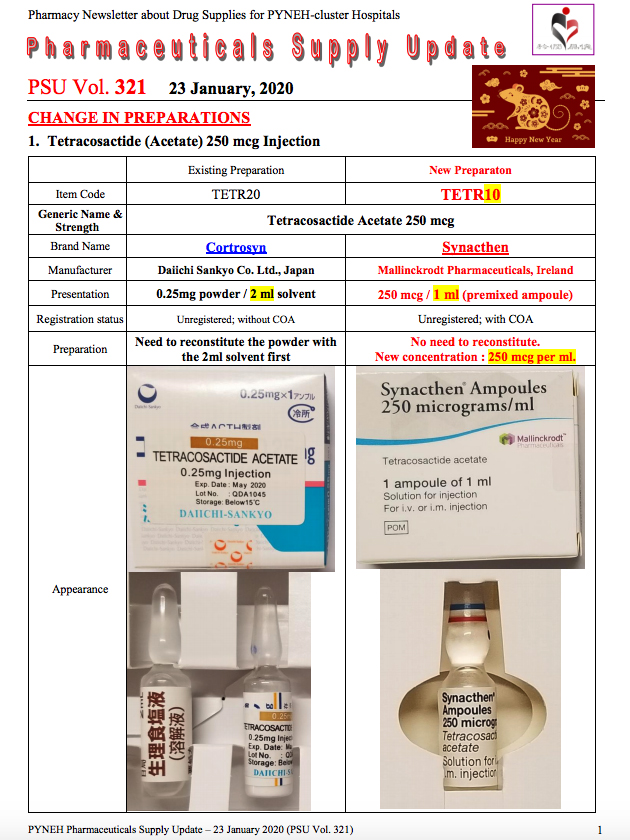

In addition, tracing a notice circulated in Eastern Hospital on January 23, FactWire investigated the change of ‘Cortrosyn’ made by Japan’s Daiichi Sankyo to ‘Synacthen’ made in Ireland’s Mallinckrodt Pharmaceuticals. Neither the former nor the latter has been registered in Hong Kong.

In the notice, ‘Cortrosyn’ is marked ‘without COA’, which likely means that the drug does not have a Certificate of Analysis. This contradicts with what is written on the Department of Health Drug Office’s website: a Certificate of Analysis issued by the manufacturer is required for importing an unregistered drug.

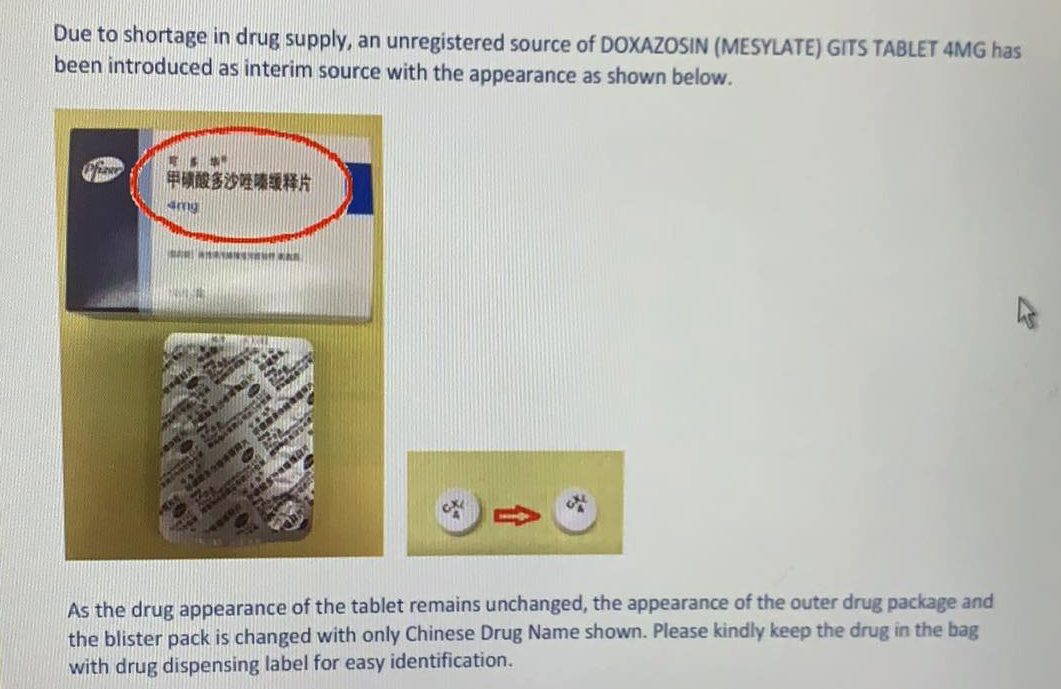

Sources tell that this is not a new phenomenon: public hospitals in Hong Kong have long been using drugs originally meant for export to other places. Internal documents of Prince of Wales Hospital reveal that in May of last year, an unregistered mainland version of ‘Cardura’, a urological drug made in the U.S., was being used as interim supply. An attached photo shows that the unregistered drug’s packaging looks similar to Hong Kong’s registered version. The only difference is the simplified Chinese characters printed on its box.

According to Section 36 of the Pharmacy and Poisons Regulations, any pharmaceutical product or substance must be registered before it is sold, offered to sell, distributed, or possessed for the above or other purposes. The only exceptional cases that allow the usage of unregistered drugs are as follows: (1A)(a)(i)(b) for export; (1A)(a)(ii) for manufacturing or compounding pharmaceutical preparations; (1A)(c)(d) for administering in clinical trials or medicinal tests; and (1A)(ab) for treating particular patients or particular animals by registered medical, veterinary and dental practitioners.

The latter route, known as the ‘Named Patient’ programme, is how unregistered substitutions of common drugs have been imported. This is a practice William Chui Chun-ming, the president of the Society of Hospital Pharmacists of Hong Kong confirms. He noted that the Hospital Authority uses the ‘Named Patient’ route not only when importing special drugs, but also when the supply of common drugs runs out.

The Authority only does so when there is “no choice for them”, said Chui, “A lot of work is required indeed, including declaring the number of bottles, information of the patient, the time frame of using it, and so on.”

However, the president of the Hong Kong Public Doctors’ Association Arisina Ma Chung-yee found it “strange” to introduce common drugs such as antibiotics through this channel. The ‘Named Patient’ programme is usually used for drugs that are new or for the treatment of rare diseases.

“Say for example ten boxes of unregistered drugs are imported using the Named Patient method. Meaning, there is a list of named patients who are allowed to consume these ten boxes. But if those are antibiotics, it is hard to limit its use to only the list of named patients. Antibiotics are so commonly used – even when there is a new patient in emergency,” she said, thus pointing out that the programme is not designed for importing common drugs.

Another issue is the claimed shortage supply of commonly used drugs. William Chui suggested three major reasons leading to drug shortage: the shortage of raw materials, contaminated batches of drugs, and/or manufacturers who stop registering in Hong Kong. “Drug manufacturers do not just cater Hong Kong’s favor. They register only when there are business opportunities. For instance, Japan has a bigger population than Hong Kong. Manufacturers may thus lose interest in Hong Kong,” said Chui.

However, Dr. Ma told FactWire that she questions why a shortage of commonly used drugs even exists. “Commonly used drugs are often manufactured by many companies. Why would there be a shortage so serious that only unregistered manufacturers can supply that common drug?”

A source from inside a drug manufacturer told FactWire that this practice possibly originates with the manufacturing company itself. When manufacturers cannot supply drugs on time, they are required to pay the Hospital Authority the extra amount for purchasing substitutes. “From the manufacturer’s point of view, it is unbeneficial to pay extra. Why not simply take those from another country but produced by the same manufacturer then?” The source gave an example of a drug in Hong Kong that is sold at the same price in Singapore. Thus the manufacturer would not have to incur any extra costs.

The Hospital Authority gives priority for certain unregistered drugs, the insider explained. When an original drug is in shortage, the Hospital Authority prioritises drugs produced by the same manufacturer over alternatives in the market – even if it is unregistered – to ensure that the drug ingredients remain the same.

Receiving allowance for the unregistered drugs to be imported requires the manufacturers to submit test reports, packaging and samples to the Hospital Authority. The Authority, at the same time, prepares a list of named patients who will be using that drug, then applies for an import permit from the Department of Health. The entire procedure takes roughly a month to complete.

In addition, there exists the issue of knowledge and transparency about these unregistered drugs. William Chui claimed that pharmacists and dispensers seldom inform patients of the registration information because most patients are more concerned about the drug’s effectiveness. ‘They would think: I wouldn’t know even if you weren’t telling me. Why do you have to tell me? It’s okay as long as you are not making a mistake.”

Nevertheless, Dr. Ma said that it is both the patient’s right to know whether or not the drug is registered and the doctor’s obligation to inform their patients about the drug’s status. “It is my responsibility as a doctor to give prescriptions. But if the quality of the drugs is in fact not up-to-standard, and if it is unregistered, would it then still be my responsibility to prescribe?”

Despite the fact that doctors are sometimes notified by the pharmacy of the change in packaging, Dr. Ma noted that doctors cannot determine from the prescription system whether a particular drug has been registered or replaced. She told FactWire that the Central Coordinating Committee of each specialist area is responsible for discussing and arranging imports of new drugs using the ‘Named Patient’ programme. Doctors of each corresponding specialist area are made aware of the new unregistered drugs being introduced, but it is not the case to inform them of unregistered common drug replacements.

Like Dr. Ma, the safety of unregistered drugs was an issue that concerned Tim Pang Hung-cheong of the Society for Community Organisation. He disagreed with the use of the ‘Named Patient’ programme in importing commonly used drugs and suggested there can be better solutions for the shortage of common drugs.

Although the impact of using unregistered drugs may not have been fully revealed, Pang believed there to be a risk for patients. ‘There is always a risk if the drug is unregistered in Hong Kong. If something special happens to patients while using the drug, the patient should at least know that it is unregistered and be able to inform their doctor or the hospital.”

He added that doctors can reassure patients by clearly communicating the reasons for prescribing an unregistered drug and about the safety tests that unregistered drugs must pass.

FactWire has sent multiple enquiries to the Hospital Authority about the usage of unregistered drugs, including the details on the drugs mentioned in this article. These requests were made according to Code on Access of Information. The Authority declined such requests by claiming that “no centralised record is available”.

When asked whether the unregistered drugs mentioned above have been administered, the Authority restated that drugs’ quality and safety are priorities, without giving a clear answer about whether or not the drugs have been administered.

“Certain types of registered drugs may be in shortage at times. As to ensure patients receive the most appropriate treatment, unregistered drugs may be imported to public hospitals when there is no alternative. If the labels are not in English, the hospital pharmacists will notify and explain to front-line medical staff the correct use of the drugs,” said the Authority.

It did not comment on whether or not doctors and patients are informed about the unregistered status of certain drugs in Hong Kong.

FactWire also contacted the Department of Health, inquiring about import permits of the above-mentioned unregistered drugs. The Department said it “involves commercial information” and refused to provide relevant information.

It added that any pharmaceutical product to be sold in Hong Kong must be up to safety, efficacy and quality standards, and must be registered by the Pharmacy and Poisons Board of Hong Kong according to that board’s regulations. It claimed that while the regulations also do allow registered medical practitioners to import, possess and use unregistered drugs for treating specific patients, the Department of Health follows the system to issue approvals depending on cases. From the Department’s data, 11,700 relevant permits have been issued from 2018 to 2019.

FactWire requested the number and lists of permits allowing unregistered-drug imports in the past five years, by again citing the Code on Access of Information. The Department of Health declined the request by saying “unreasonable use of the Department’s resources is needed to provide relevant information”, and “the incomplete or yet-to-complete information may mislead people, or deprive related departments and others of their priority to first reveal the information and their commercial benefits.”

While the Department of Health encourages the public to only buy drugs registered in Hong Kong, information is difficult to retrieve. The database for registered drugs is openly available on the Drug Office’s website, but it is limited to only showing the drug’s commercial name, main ingredients, company holding its registration and its address in Hong Kong. Despite the database being openly available, without the details mentioned above, it is difficult to obtain any meaningful information.